Recently Twitter has been ablaze with a back-and-forth discussion around the question of English identity and how it is defined. Conservative Leadership candidate Robert Jenrick held a frankly embarrassing interview with Sky News’ Matt Barbet in which he repeatedly failed to give an adequate definition of English identity when interrogated on the matter.

The issue with the “what does it mean to be English anyway?” line of questioning is that it’s a trap. No answer will ever be good enough because ethnic identity is not something that can be given the sort of Socratic definition that the question presupposes.

Socratic definitions are definitions that attempt to distil the essence of a thing in such a way that it can be reduced to a clear, rational, and objective statement. This can be quite useful when formulating mathematic proofs or working with problems of logic, but it cannot be easily applied to more complex issues such as identity. What’s a triangle? It’s a shape with three sides and three corners. Simple enough. What’s a quadrilateral? It’s a shape with four sides and four corners. What’s a rectangle? It’s a shape with four sides, and four corners all of which are right angles. What’s a square? It’s a shape with four sides of equal length, and four corners which are all right angles.

We can see how it works. A rectangle is a specific type of quadrilateral, and a square is a specific type of rectangle. These definitions are very clear, very simple, and do not leave any room for interpretation or complication.

So far, so good. But when we attempt to apply this rational method to more complex phenomena, we run into problems. What is a knife? It’s a man-made instrument used for cutting things. Simple enough, isn’t it? Well, no. By this definition, a saw would be considered a type of knife, as would a sword. Since these things are clearly not knives, the definition must be made more specific in order to exclude them.

I decided to ask ChatGPT for a definition of ‘knife’ which makes clear the distinction and excludes other cutting instruments such as saws and swords. This is what it gave me: ‘A knife is a hand-held tool with a sharp, single-edged blade, typically used for precise cutting tasks in domestic, hunting, or craft-related contexts, distinguished from saws by its smooth blade and from swords by its general utility and shorter length.’

Sounds good. But this raises issues too. A butter knife is specifically designed not to be sharp, and in any case, a once-sharp knife which has now become dull is still a knife. Isn’t a dagger technically a kind of knife? But a dagger has two sharp edges. Some knives do not have smooth blades, but serrated blades, such as bread knives. A machete is a type of knife isn’t it? But some machetes are longer than swords. Is a scalpel a knife? Exploring the inadequacies of definitions can be a pretty good way to train your skills of logic, and I do recommend you try it. Be careful, though, because such deconstruction can be taken too far, and can be used for nefarious purposes. Attempts at the sort of autistic precision which Socratic definitions demand tend to lead to a spiral effect where eventually the definition either becomes so unwieldy or so absurd that it ceases to function as a descriptive term. If something as seemingly simple as the definition of a knife is so complicated, how can one be expected to define English identity in a simple soundbite? This is what our opponents rely on: “Well, if you can’t define it, what are you even talking about? Why should anyone take your complaints about the ‘loss of English identity’ seriously when you can’t even tell us what it is?”

You’ve probably heard the story where Plato defined man as a ‘featherless biped’. Diogenes, hearing of this, plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato’s academy, declaring: “Behold! Plato’s man!” The definition was then changed to ‘a featherless biped with broad, flat nails’. In a bland, materialistic, taxonomic sense, this is adequate, but let’s be honest, the essence of man is far larger and far more complex ‘a featherless biped with broad, flat nails’.

If we tried to operate in the world using strictly Socratic definitions for objects and concepts, nothing would ever get done; nobody could ever have a proper conversation; no systems could ever function. It’s clear that this rationalistic mode of thinking has its proper purpose, but it cannot be applied ubiquitously in human life.

Returning to the topic of English identity, the debate over the last couple of days has shown that all answers along the lines of values, history, architecture, art, and so on, will be met with mockery and deconstructed into absurdity. It’s best to step over the question entirely.

One very telling aspect of this debate is the fact that even 20 years ago it would have seemed absurd. Our enemies will laugh at us for complaining that English identity is under threat, in full knowledge that it is, since they’re the ones consistently attacking it. But their feigned ignorance is proving very useful in this debate. Similar to the “what is a woman?” question from a few years back, it is a very powerful tactic to ask a difficult-to-answer question, sit back, and let your interlocutor make a fool of themselves. And that’s the issue with this debate: attempting to answer this question within the rationalistic paradigm of the modern day, in a form that cannot be deconstructed into absurdity, is basically impossible.

If we talk about English history, well, you weren’t there. It wasn’t anything to do with you. (It’s interesting how this standard somehow doesn’t apply when the topic is colonisation though, isn’t it?). If we talk about architecture, well, it’s just a building. What, you define your identity based on bricks? If we talk about food—well, let’s not even go there.

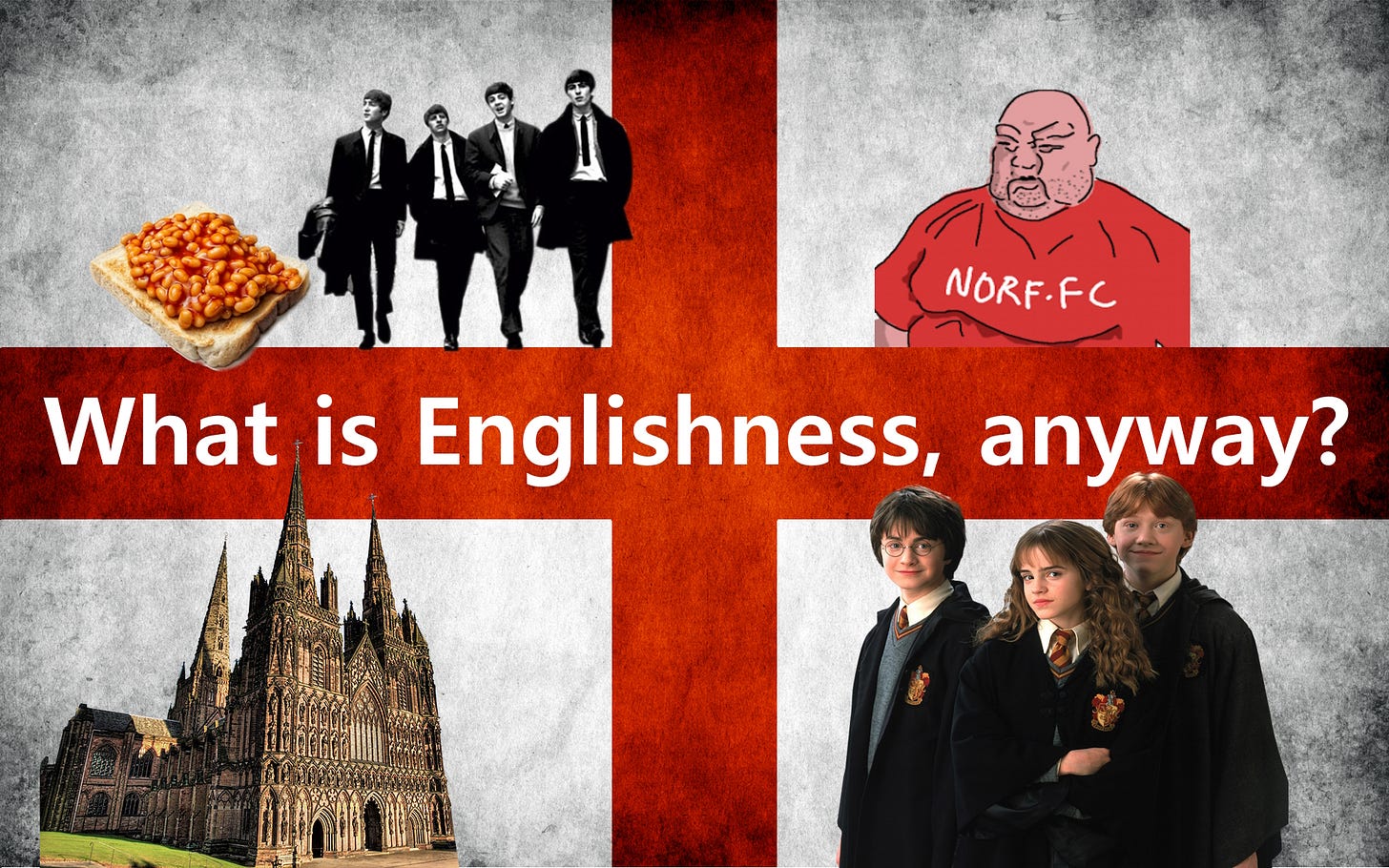

With regard to certain cultural landmarks, these are hardly more useful. I’ve never seen a James Bond film. I hate baked beans. Most younger Englishmen hardly know who The Beatles are beyond the fact that they’re some old band that old people like. The notion of Englishness predates the Harry Potter series. These things are expressions of Englishness, but they are only material symbols in a vast, vast web of Englishness, so they’re pretty useless for defining it. They do not get to the essence of Englishness, and are absurd as answers in the rationalist paradigm which the question sets up.

I think a large part of the issue is the United Kingdom itself. Englishness has been subsumed into Britishness in a way that Welsh and Scottish identity have not. I won’t get into that now—I’m sure there’s a David Starkey video exploring that with far more authority than I can claim—but I’m certain this, and the British Empire more generally, has a lot to do with the difficulty of pinning down English identity.

In conclusion, the people posing this question are incapable of thinking in terms of transcendence, metaphor, or any other non-material sense and it’s a waste of your time to attempt to make them understand. Remember when Just Stop Oil protestors attacked Stonehenge and the response from their fellow leftists was “why are you upset about someone spraying orange paint on a pile of stones?” They are consciously ignorant of the deeper meaning that the ‘pile of stones’ represent, and their purely materialistic and rationalistic thinking prevents them from feeling any sort of sentimental attachment to such symbols.

It’s a losing game, and we must stop playing it. Step over it. Ask them why they want to erase your identity. Ask them why they know perfectly well what an Englishman is when they are castigating you for the sins of your imperial ancestors. Do not engage in this dialectical game. When a battle is unwinnable—as it seems this one is, due to the paradigm we are in—cut your losses. Step over it, go around it. Do not engage with them on their terms; reframe the debate, or sidestep it entirely.

Common-law. Free speech. Equality. Habeus Corpus. Most of the popular sports in the entire world. Taking the piss.

Oh, and 75% of indigenous English can trace their matrilineal DNA back 5,000 years.

Of course it’s mostly to do with ethnocultural heritage. It’s just that anyone who isn’t actively anti-white is too terrified to assert that the indigenous peoples of Britain and its historically settled population have any special claim to it because this threatens the whole deck of cards which is multicultural Britain.

Of course, the same standards are not applied to others. 2nd or 3rd level immigrants are encouraged to celebrate their own ethnocultural identity. But why do they need to if they are “just as British” as you or me?