Ted Kaczynski: The Power Process and Surrogate Activities (TK2)

Analysing the Unabomber manifesto

In the first instalment of this series on Industrial Society and its Future, we covered the first half of Kaczynski’s analysis of the psychology of Leftism. This time around we’ll get into the meat of Kaczynski’s concepts of the ‘power process’ and ‘surrogate activities’ and how these relate to his view of the detrimental and dehumanising nature of industrial society.

The Power Process

33. Human beings have a need (probably based in biology) for something that we will call the power process. This is closely related to the need for power (which is widely recognized) but is not quite the same thing. The power process has four elements. The three most clear-cut of these we call goal, effort and attainment of goal. (Everyone needs to have goals whose attainment requires effort, and needs to succeed in attaining at least some of his goals.) The fourth element is more difficult to define and may not be necessary for everyone. We call it autonomy and will discuss it later.

34. Consider the hypothetical case of a man who can have anything he wants just by wishing for it. Such a man has power, but he will develop serious psychological problems. At first he will have a lot of fun, but by and by he will become acutely bored and demoralized. Eventually he may become clinically depressed. History shows that leisured aristocracies tend to become decadent. This is not true of fighting aristocracies that have to struggle to maintain their power. But leisured, secure aristocracies that have no need to exert themselves usually become bored, hedonistic and demoralized, even though they have power. This shows that power is not enough. One must have goals toward which to exercise one’s power.

35. Everyone has goals; if nothing else, to obtain the physical necessities of life: food, water and whatever clothing and shelter are made necessary by the climate. But the leisured aristocrat obtains these things without effort. Hence his boredom and demoralization.

36. Non-attainment of important goals results in death if the goals are physical necessities, and in frustration if non-attainment of the goals is compatible with survival. Consistent failure to attain goals throughout life results in defeatism, low self-esteem or depression.

37. Thus, in order to avoid serious psychological problems, a human being needs goals whose attainment requires effort, and he must have a reasonable rate of success in attaining his goals.

So, what Kaczynski is saying here is that the root of what we consider to be mental illness lies in a disruption of the power process—later on in the manifesto it will be discussed that mental illness is itself defined in relation to the industrial system. That is to say, activities, behaviours, and states of mind which do not adhere to the ideology of (or suit the functioning of) the system are considered mental illness. In this is shown just one manifestation of the way that industrial society pervades every single aspect of life, from the more obvious social, political, and economic facets, to the less easily perceptible—the architectural, the psychic, the vocational, the chronological, and the spiritual.

In ‘Capitalist Realism’, a fantastic 2009 study on the all-pervasive nature of capitalism beyond its place as an economic system, Mark Fisher comments on the widespread nature of mental unwellness in capitalist society, saying “We need to ask: how has it become acceptable that so many people, and especially so many young people, are ill? The ‘mental health plague’ in capitalist societies would suggest that, instead of being the only social system that works, capitalism is inherently dysfunctional, and that the cost of it appearing to work is very high.”

As Kaczynski outlines it, the power process goes like this: firstly, having a goal, secondly, putting in the effort to attain that goal, and finally, attaining it. Autonomy, the fourth element, is important for many—though not all—people, as most are unable to properly fulfil the power process unless their goal and the method by which they attain it are chosen and acted out of their own volition.

He proposes that the power process is deeply rooted in human biology, since the non-attainment of goals, when those goals are physical necessities (as they were for the vast majority of human history), results in death. The power process is not something that can ever be ‘completed’, it is a constantly recurring process which plays a massive role in human life and psychic wellbeing. As Kaczynski notes, the man who has everything he could ever want would, unless he filled his time with surrogate activities, eventually be made terribly depressed due to this state of being. Ted will go on to describe later how the industrial revolution has led to a massive disruption of the power process, thus causing the widespread mental health issues that characterise the modern age.

Surrogate Activities

38. But not every leisured aristocrat becomes bored and demoralized. For example, the emperor Hirohito, instead of sinking into decadent hedonism, devoted himself to marine biology, a field in which he became distinguished. When people do not have to exert themselves to satisfy their physical needs they often set up artificial goals for themselves. In many cases they then pursue these goals with the same energy and emotional involvement that they otherwise would have put into the search for physical necessities. Thus the aristocrats of the Roman Empire had their literary pretensions; many European aristocrats a few centuries ago invested tremendous time and energy in hunting, though they certainly didn’t need the meat; other aristocracies have competed for status through elaborate displays of wealth; and a few aristocrats, like Hirohito, have turned to science.

39. We use the term “surrogate activity” to designate an activity that is directed toward an artificial goal that people set up for themselves merely in order to have some goal to work toward, or, let us say, merely for the sake of the “fulfillment” that they get from pursuing the goal. Here is a rule of thumb for the identification of surrogate activities. Given a person who devotes much time and energy to the pursuit of goal X, ask yourself this: If he had to devote most of his time and energy to satisfying his biological needs, and if that effort required him to use his physical and mental faculties in a varied and interesting way, would he feel seriously deprived because he did not attain goal X? If the answer is no, then the person’s pursuit of a goal X is a surrogate activity. Hirohito’s studies in marine biology clearly constituted a surrogate activity, since it is pretty certain that if Hirohito had had to spend his time working at interesting non-scientific tasks in order to obtain the necessities of life, he would not have felt deprived because he didn’t know all about the anatomy and life-cycles of marine animals. On the other hand the pursuit of sex and love (for example) is not a surrogate activity, because most people, even if their existence were otherwise satisfactory, would feel deprived if they passed their lives without ever having a relationship with a member of the opposite sex. (But pursuit of an excessive amount of sex, more than one really needs, can be a surrogate activity.)

The epidemic of young men who waste the entirety of their free time playing video games is one glaring example of the disruption of the power process in society. As many children now grow up with single mothers, as masculinity has been declared ‘toxic’, and as relations between the genders have become ever more strained due to cultural phenomena such as feminism, boys and young men with no other avenue to fulfil the power process now turn to video games as their preferred surrogate activity.

Gaming is the surrogate activity without rival. The colourful animations, the neuro-psychological tricks employed to keep players enticed (rewards given just often enough and at just the right moment to maximally light up the pleasure and reward systems in the brain), the opportunity to ‘experience’ things which would be either impossible or functionally impossible in the real world; all of this combined with a massive prevalence of parents who are afraid to let their children play outside, and would therefore actually prefer for them to waste away in their rooms, is a recipe for disaster.

As more children spend their youths isolated indoors, they do not properly develop; they become little Peter Pans who will never grow up, and their social skills are sorely lacking. Many Gen Z youths are essentially being made functionally autistic; their attention span is non-existent without a constant deluge of stimuli, and they have nothing to talk about—and no conversational skills in any case. Worst of all, it is a self-reinforcing phenomenon; the fewer kids there are playing outside, the fewer kids there are for other kids to play outside with.

Perhaps the saddest aspect of the use of video games as a surrogate activity is that it imparts no tangible benefit on the participant. At least history nerds, musicians, bodybuilders, and chess players are learning a skill, expanding their knowledge, or improving their physical health. But people find goals to work towards and a sense of autonomy in video games that seem to no longer be provided by the real world. As virtual reality technology develops further, this problem will only be exacerbated.

40. In modern industrial society only minimal effort is necessary to satisfy one’s physical needs. It is enough to go through a training program to acquire some petty technical skill, then come to work on time and exert the very modest effort needed to hold a job. The only requirements are a moderate amount of intelligence and, most of all, simple obedience. If one has those, society takes care of one from cradle to grave. (Yes, there is an underclass that cannot take the physical necessities for granted, but we are speaking here of mainstream society.)

The modern concept of work, wherein one is paid an hourly wage in exchange for providing his labour to a corporation, is intensely alienating for many, if not most, people—and it is particularly troubling for those whose need for autonomy is relatively high. The division of labour, while planting the seed for the incredible growth of industrialised economies, is simultaneously the aspect of modern labour which makes it so chronically unfulfilling.

While the production output of factories is massively increased when one worker puts one screw into one part of a machine on the production line, ad nauseum, every single worker on the production line is alienated from the experience of actually creating the machine or product in question. Yes, such a system is economically efficient; yes, such a system reduces poverty; but it also reduces those involved to minute cogs in a behemoth of a machine—easily interchangeable parts which are individually unimportant relative to the whole system.

Just as the screw is interchangeable with any other screw of the same type, so is the production-line worker interchangeable with any other production-line worker. The worker becomes fungible—just another commodity, another input required to produce an output, alongside the raw materials and machinery. As the job is so simple that practically anybody could do it, they have no bargaining power and are at the mercy of their employer. Not only is the work unfulfilling and monotonous, but it leaves absolutely no room for creativity or autonomy.

But we in the West mostly outsourced our industrial production to the Third World decades ago. The average worker in our society either works a service job, or else performs some form of manual labour. Those working in shops assisting customers or working in offices answering emails are also alienated, though their duties generally allow for a little more creativity than manufacturing. Nevertheless, the shop assistant is standing in somebody else’s shop (‘somebody’ they will never meet), selling somebody else’s products (almost all of which are produced abroad), to somebody they will never see again. Everybody is a ‘somebody’—and yet a ‘nobody’—in a world where true and meaningful human connection has been dissolved by distance and anonymity.

The nine-to-five office worker spends half of his waking hours in the office of a faceless multinational corporation, answering the questions of a customer they will never see, about a product they have never seen, on behalf of a company which would replace them in a heartbeat.

Later we will discuss some of the ways in which we are expected to adapt to the needs of the system, rather than creating an economic arrangement adapted to our needs.

Thus it is not surprising that modern society is full of surrogate activities. These include scientific work, athletic achievement, humanitarian work, artistic and literary creation, climbing the corporate ladder, acquisition of money and material goods far beyond the point at which they cease to give any additional physical satisfaction, and social activism when it addresses issues that are not important for the activist personally, as in the case of white activists who work for the rights of nonwhite minorities.

These are not always pure surrogate activities, since for many people they may be motivated in part by needs other than the need to have some goal to pursue. Scientific work may be motivated in part by a drive for prestige, artistic creation by a need to express feelings, militant social activism by hostility. But for most people who pursue them, these activities are in large part surrogate activities. For example, the majority of scientists will probably agree that the “fulfillment” they get from their work is more important than the money and prestige they earn.

41. For many, if not most, people, surrogate activities are less satisfying than the pursuit of real goals (that is, goals that people would want to attain even if their need for the power process were already fulfilled). One indication of this is the fact that, in many or most cases, people who are deeply involved in surrogate activities are never satisfied, never at rest. Thus the money-maker constantly strives for more and more wealth. The scientist no sooner solves one problem than he moves on to the next. The long-distance runner drives himself to run always farther and faster. Many people who pursue surrogate activities will say that they get far more fulfillment from these activities than they do from the “mundane” business of satisfying their biological needs, but that is because in our society the effort required to satisfy the biological needs has been reduced to triviality. More importantly, in our society people do not satisfy their biological needs autonomously but by functioning as parts of an immense social machine. In contrast, people generally have a great deal of autonomy in pursuing their surrogate activities.

A fascinating point is raised here: namely, that we possess more autonomy in the pursuit of surrogate activities than in the biological needs that they are substituting in the power process. Ted is also correct that since surrogate activities are not deeply satisfying, we are never truly at rest. If you’ve ever worked a manual labour job you’ll have probably had the feeling of contentment after a particularly hard day’s work, where you are perfectly happy to sit and do nothing when you arrive home—feeling no need to reach for the video games or the television remote.

Autonomy

42. Autonomy as a part of the power process may not be necessary for every individual. But most people need a greater or lesser degree of autonomy in working toward their goals. Their efforts must be undertaken on their own initiative and must be under their own direction and control. Yet most people do not have to exert this initiative, direction and control as single individuals. It is usually enough to act as a member of a small group. Thus if half a dozen people discuss a goal among themselves and make a successful joint effort to attain that goal, their need for the power process will be served. But if they work under rigid orders handed down from above that leave them no room for autonomous decision and initiative, then their need for the power process will not be served. The same is true when decisions are made on a collective basis if the group making the collective decision is so large that the role of each individual is insignificant.

43. It is true that some individuals seem to have little need for autonomy. Either their drive for power is weak or they satisfy it by identifying themselves with some powerful organization to which they belong. And then there are unthinking, animal types who seem to be satisfied with a purely physical sense of power (the good combat soldier, who gets his sense of power by developing fighting skills that he is quite content to use in blind obedience to his superiors).

44. But for most people it is through the power process—having a goal, making an autonomous effort and attaining the goal—that self-esteem, self-confidence and a sense of power are acquired. When one does not have adequate opportunity to go through the power process the consequences are (depending on the individual and on the way the power process is disrupted) boredom, demoralization, low self-esteem, inferiority feelings, defeatism, depression, anxiety, guilt, frustration, hostility, spouse or child abuse, insatiable hedonism, abnormal sexual behavior, sleep disorders, eating disorders, etc.

Sources of Social Problems

45. Any of the foregoing symptoms can occur in any society, but in modern industrial society they are present on a massive scale. We aren’t the first to mention that the world today seems to be going crazy. This sort of thing is not normal for human societies. There is good reason to believe that primitive man suffered from less stress and frustration and was better satisfied with his way of life than modern man is. It is true that not all was sweetness and light in primitive societies. Abuse of women was common among the Australian aborigines, transsexuality was fairly common among some of the American Indian tribes. But it does appear that generally speaking the kinds of problems that we have listed in the preceding paragraph were far less common among primitive peoples than they are in modern society.

46. We attribute the social and psychological problems of modern society to the fact that that society requires people to live under conditions radically different from those under which the human race evolved and to behave in ways that conflict with the patterns of behavior that the human race developed while living under the earlier conditions. It is clear from what we have already written that we consider lack of opportunity to properly experience the power process as the most important of the abnormal conditions to which modern society subjects people. But it is not the only one. Before dealing with disruption of the power process as a source of social problems we will discuss some of the other sources.

47. Among the abnormal conditions present in modern industrial society are excessive density of population, isolation of man from nature, excessive rapidity of social change and the breakdown of natural small-scale communities such as the extended family, the village or the tribe.

48. It is well known that crowding increases stress and aggression. The degree of crowding that exists today and the isolation of man from nature are consequences of technological progress. All pre-industrial societies were predominantly rural. The Industrial Revolution vastly increased the size of cities and the proportion of the population that lives in them, and modern agricultural technology has made it possible for the Earth to support a far denser population than it ever did before. (Also, technology exacerbates the effects of crowding because it puts increased disruptive powers in people’s hands. For example, a variety of noise-making devices: power mowers, radios, motorcycles, etc. If the use of these devices is unrestricted, people who want peace and quiet are frustrated by the noise. If their use is restricted, people who use the devices are frustrated by the regulations. But if these machines had never been invented there would have been no conflict and no frustration generated by them.)

I have made clear my thoughts in other essays on the topic of modern urban living. The city is draining, alienating, soul-destroying, and unnatural.

49. For primitive societies the natural world (which usually changes only slowly) provided a stable framework and therefore a sense of security. In the modern world it is human society that dominates nature rather than the other way around, and modern society changes very rapidly owing to technological change. Thus there is no stable framework.

This point cannot be understated. The stability and slow pace of change in pre-industrial society provided security to the people within it. It will also have inspired a lot of long-term thinking and planning into those people; having to plan ahead for the winter, ensuring enough supplies to get through those long, dark months. I said earlier that one of the less perceptible ways in which industrial society pervades every single aspect of life was ‘chronological’. In pre-industrial society, we did not have to constantly check our watches; we did not wake up to digital alarm clocks; people arranged to meet ‘at dawn’, ‘at midday’, ‘at dusk’. I truly believe that the application of millisecond-accurate time-keeping to our lives—while efficient and practical—is the cause of much unconscious psychic stress.1

50. The conservatives are fools: They whine about the decay of traditional values, yet they enthusiastically support technological progress and economic growth. Apparently it never occurs to them that you can’t make rapid, drastic changes in the technology and the economy of a society without causing rapid changes in all other aspects of the society as well, and that such rapid changes inevitably break down traditional values.

This is a great point, though I would push back slightly and simply state that it is not only conservatives who are very enthusiastic about technology and the possibilities it affords; more specifically, those most enthusiastic about technology are often Leftists—think progressive Californian tech-bros. Though I admit he is correct—after all, it is not the Leftists who are disappointed by the decay of traditional values. Many small-c conservatives and basically all capital-C Conservatives fall into the ‘pro-technology’ camp, being optimistic about the potential of technology in increasing efficiency of production and spurring economic growth.

But to demand constant economic growth while resisting social change is folly; it is for this reason that in order to uphold a properly traditional social order, society must be reoriented around an economic system which favours subsidiarity over efficiency, stable family and community relations over growth, tradition over innovation, and meaningful labour rather than corporate profit. The monomaniacal concern for GDP growth above all else is one of the significant causes of many of our most pressing political issues (mass immigration, national debt accumulation, social atomisation, community breakup, environmental destruction, et cetera). Our economic arrangement must be subservient to the wellbeing of humans, not the other way around.

Personally, I tend to lean towards the ‘anti-technology’ or, at least, ‘technology-sceptic’ camp, which forms a large part of my distributist and localist leanings. Kaczynski is correct that there is an inherent contradiction between technological progress and tradition, which I and presumably most other anti-capitalist social conservatives acknowledge.

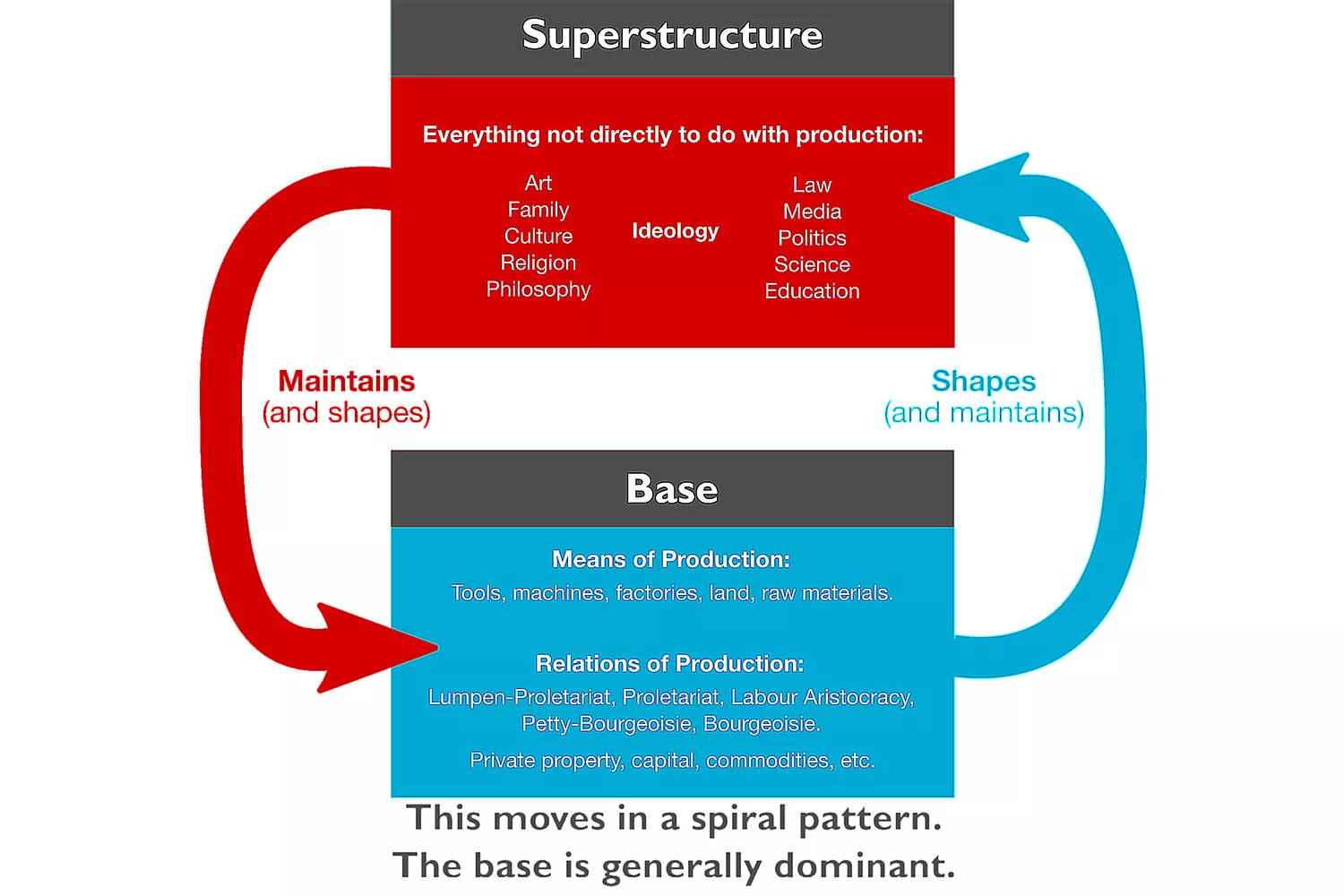

Technology and culture are deeply interwoven. This is one area in which Karl Marx was surprisingly correct; the material conditions of a society (the base) are a major factor in determining the cultural ‘shape’ of a society (its superstructure), and that culture simultaneously influences the development of its material conditions.

To use a concrete modern example, a standard 12-inch vinyl record can hold roughly 22 minutes of music per side, giving a total of 44 minutes of runtime. In previous decades, when vinyl records were the only or main form of music storage, these material conditions essentially restricted musicians to producing albums with a total length of no more than 44 minutes (or double albums of no more than 88).

When the compact disc was being developed, there was debate over which size should be set as the standard size: 11.5cm or 12cm. Eventually it was decided that, in order that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony could be held in its entirety on one CD—to be listened to without interruption—the standard size would have to be 12cm, which is capable of holding around 74 minutes’ worth of music. This is an example of a society’s artistic culture playing a role in the shaping and development of its material conditions.

Now, in the modern era of on-demand streaming, artists are free to produce albums which are as long or as short as they desire. There are essentially no material restrictions on an album’s length, and artists who want to release very short albums can do so without worrying about fans feeling ‘ripped off’ at paying full price for a small amount of content.

Those of us on the right would do well to take into account the insights of influential Leftists, even if only to understand the enemy; though it is often helpful to look at things in a new light and consider if the creations of the enemy may be suitable if co-opted to aid our cause. Perhaps work could be done to apply the framework of dialectical materialism to our current state of affairs to see if it could provide an avenue to furthering our goals. It’s worth a try, at least.

Now, onto a different example of technology’s impacts on culture and society: the exponential rise of gender confusion. Connor Tomlinson of the Lotus Eaters—channelling Ivan Ilych—speaks often of transgenderism as a phenomenon which could only exist in anything more than a negligible form, in a society which possesses an amount of technology sufficient to estrange the masses from their physical bodies with its machines, and which thereby diminishes the importance of sex differences.

For example, due to the invention of the washing machine, the ubiquity of fast food and frozen meals, the automation of many manual labour tasks and factory jobs, the shift to a service economy, and so on, many working- and middle-class men and women now work side-by-side in offices. They perform the same tasks and the same functions in their daily lives, and are essentially the same. With sex differences largely overcome in the modern workplace, culture has seen a shift in which a portion of the population take on hyper-real sexual forms—presenting a warped simulation of masculinity and femininity.

To use two trivial examples, Deano, (the dim-witted but well-meaning archetype of post-modern masculinity) may set about building unnaturally large muscles which could only be achieved due to the extent of leisure time available for him to engage in concentrated exercise, and an intake of calories which would not have been available to the eighteenth century peasant. Mrs. Deano may enjoy acrylic nails which would have made the work of a woman in earlier times quite difficult - preparing meals, knitting and sewing, childrearing, and so on.

Modern plastic surgery, originally developed to treat horribly disfigured soldiers following the Great War, has now become synonymous with facelifts, breast augmentation, and the Kardashians. The substance of sex differences has been essentially erased, and the form is all that remains; untethered to the necessities of daily life in pre-modern times, these features can be inflated to an unnatural extent for purely aesthetic purposes.

Human sex differences are no longer as functionally important as they had been in previous eras. Mr. and Mrs. Deano work in the same office, doing the same job (answering the telephone, attending meetings, responding to emails, creating powerpoint presentations, and writing reports). In post-industrial society, the lie of inherent human fungibility is ubiquitous; ‘women can do anything a man can do’, and vice versa. Add to this that the popularity of the pill has created a state of affairs in which pregnancy is now a decision to be chosen rather than a fact of life, and their sex differences come to be widely perceived as superficial, and thus can be exaggerated in a way that the constraints of manual labour and the material conditions of the past would not have allowed.

Now, in a culture where material conditions allow sex differences to be perceived as only surface-level, the ground has been laid for a phenomenon such as transgenderism. This is helped along by social programming which actively de-emphasises sex differences in the service of achieving ‘equality’ and which simultaneously sends the message that one can be ‘whatever you want to be’. If a teenage girl feels uncomfortable in her changing body (as literally every teenage girl does) and thinks she would be more comfortable as a boy, there is—as far as our society is concerned—nothing stopping her. Well, except for transphobic bigotry, naturally. Adolescent transition is literally encouraged by the left-wing.

All she needs to do is take some ‘T’, wear hoodies, procure a double mastectomy to remove her still-developing breasts, undergo a skin graft on her thigh or forearm, use that skin in a phalloplasty surgery to form a ‘neopenis’, et voila! He is now a real boy.

It is the product of an entirely materialistic conception of the world that transgender activists have reduced masculinity to synthetic testosterone and muscles, and femininity to high-heels and fake tits.

The right-leaning phrase, “a woman is an adult human female” is reductive. While technically true, it is sterile, scientific language which doesn’t tell the full story. In any case, we should avoid falling into naive scientism and rationalism. There is a lot more to womanhood than having reached a certain age while possessing XX chromosomes. The path to manhood or womanhood is biologically determined as a function of our chromosomes, but the path is also played out and discovered through our embodied actions.

Feminist heroine Simone de Bouvoir once said that “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” and I’m inclined to agree. That is not to say that anyone can become a woman—only females can do that—but womanhood is something that is grown into over time, by passing through experiential and developmental milestones. There is no simple cut-off point between girlhood and womanhood; it is a process. The same, of course, applies to the path of a boy becoming a man.

Technology has made of us a society estranged from our bodies, less constrained by the particularities of the roles which our biological sex determines for us. In the capitalist system, and as a result of a series of scientific and cultural shifts, we have begun to view ourselves as essentially fungible—interchangeable with any other human—and we view our essence as being located primarily in the mind, rather than in our entire being, constituted of mind, body, and spirit. But the entirety of our conscious life—our perception—is shaped by the reality of embodiment. That is to say, the totality of our interfacing and interacting with the world is done through our physical bodies, a fact which seems to be increasingly forgotten in the digital age.

We seem to have collectively, and unconsciously, forgotten that there is, really, no such thing as a neutral ‘human’. What do I mean by this? Well, all humans are, in their essence, determined from the point of conception. Sex is one such example, as one can either be male or female; one cannot be both or neither2. This may sound like a trivial point, but males and females are inherently different from one another (only the blind ideologue could deny this), so one aspect of our being which will have large implications for the course of our life is pre-determined. The generalised differences in one’s mental and physical constitution which stem from being on one or another side of the binary in a sexually dimorphic species are already decided for us at birth. Hence, in a certain sense, it is foolish to compare men and women, to assume they are ‘the same’. It is (partly) for this reason that I reject feminism. Both sexes have their inherent advantages and disadvantages (on average) and the issues which arise by ignoring such distinctions—or attributing them solely to systems of domination—serve only to cause a severe disruption in the relations of the sexes.

If the surface form of sex differences is all that remains, devoid of metaphysical content, then technological advancements such as so-called “sex-change” surgeries and synthetic hormone treatments create the possibility for a perceived ‘change of sex’—though, of course, not a factual one. The material conditions of Western society have aligned to underlie a culture which is able to view sex and gender as fetters of domination which can be overcome if the collective wills it3. In summary, large-scale gender confusion is a thoroughly modern phenomenon, and one which could only exist in a society whose material conditions allow it. Ironically, those gender activists who profess a searing hatred of Western civilisation and bourgeois hegemony fail to recognise that the privilege of living a life in which the most pressing issue one faces is being misgendered are adherents to an ideology which simply could not exist without the leisure time and material conditions in which to deconstruct the metaphysical fundaments of reality. Talk about sawing off the branch on which one is sitting.

Back to Uncle Ted:

51. The breakdown of traditional values to some extent implies the breakdown of the bonds that hold together traditional small-scale social groups. The disintegration of small-scale social groups is also promoted by the fact that modern conditions often require or tempt individuals to move to new locations, separating themselves from their communities. Beyond that, a technological society has to weaken family ties and local communities if it is to function efficiently. In modern society an individual’s loyalty must be first to the system and only secondarily to a small-scale community, because if the internal loyalties of small-scale communities were stronger than loyalty to the system, such communities would pursue their own advantage at the expense of the system.

I have written a fair amount on this particular topic in The Spirit of Conservatism, Vol II so I’ll keep my response brief. As Ted states, in industrial society we become increasingly individualistic and atomised as family ties are broken down, as the technological system and its developments allow us, and sometimes require us, to relocate across the country or abroad. The functioning of the system requires autonomous communities to be broken up and the individuals within to be pulled into, and serve, the system.

Community ties are eroded as families come and go, and members of communities no longer feel the deep connection to their area that results from having many multiple generations of ties to it. We outsource childrearing and elderly care to the state in order to progress in our careers. Adding to this, mass migration has reduced homogeneity in a vast number of communities, which brings its own problems.

52. Suppose that a public official or a corporation executive appoints his cousin, his friend or his coreligionist to a position rather than appointing the person best qualified for the job. He has permitted personal loyalty to supersede his loyalty to the system, and that is “nepotism” or “discrimination,” both of which are terrible sins in modern society. Would-be industrial societies that have done a poor job of subordinating personal or local loyalties to loyalty to the system are usually very inefficient. (Look at Latin America.) Thus an advanced industrial society can tolerate only those small-scale communities that are emasculated, tamed and made into tools of the system.

53. Crowding, rapid change and the breakdown of communities have been widely recognized as sources of social problems. But we do not believe they are enough to account for the extent of the problems that are seen today.

54. A few pre-industrial cities were very large and crowded, yet their inhabitants do not seem to have suffered from psychological problems to the same extent as modern man. In America today there still are uncrowded rural areas, and we find there the same problems as in urban areas, though the problems tend to be less acute in the rural areas. Thus crowding does not seem to be the decisive factor.

55. On the growing edge of the American frontier during the 19th century, the mobility of the population probably broke down extended families and small-scale social groups to at least the same extent as these are broken down today. In fact, many nuclear families lived by choice in such isolation, having no neighbors within several miles they belonged to no community at all, yet they do not seem to have developed problems as a result.

56. Furthermore, change in American frontier society was very rapid and deep. A man might be born and raised in a log cabin, outside the reach of law and order and fed largely on wild meat; and by the time he arrived at old age he might be working at a regular job and living in an ordered community with effective law enforcement. This was a deeper change than that which typically occurs in the life of a modern individual, yet it does not seem to have led to psychological problems. In fact, 19th century American society had an optimistic and self-confident tone, quite unlike that of today’s society.

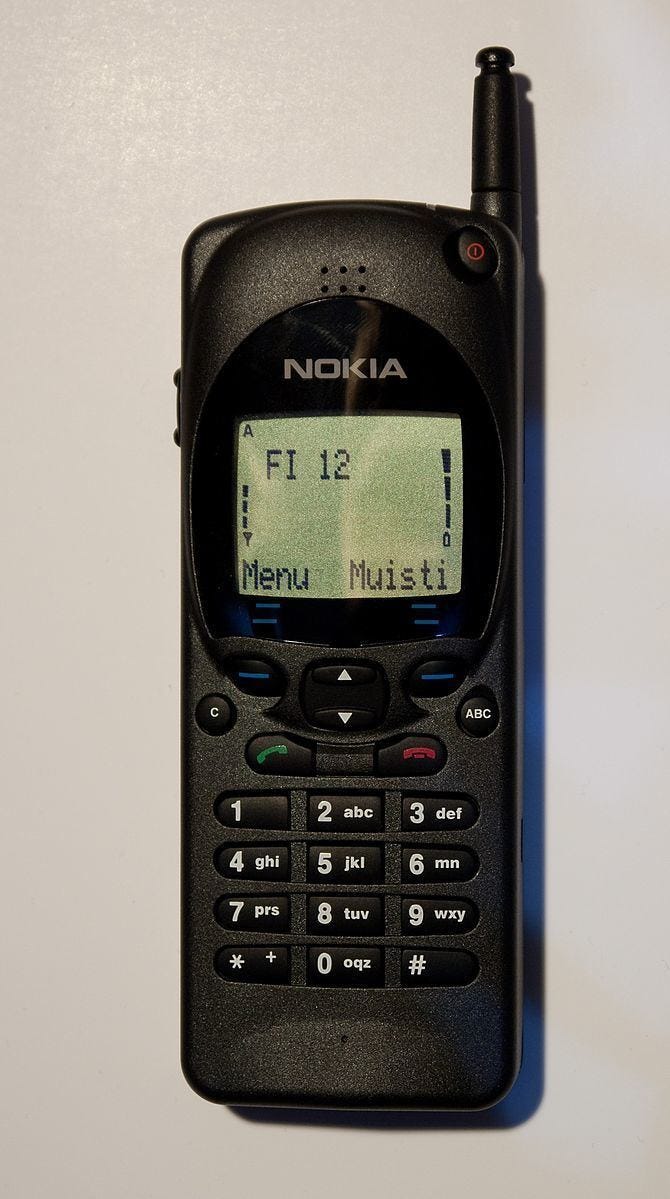

I wonder what Kaczynski would have thought of the ubiquity of mobile telephones and social media. When one ponders the question for a moment, the gargantuan leap of technology thus far in the 21st century is truly staggering. He says that the change from living in a log cabin and eating wild meat to working a regular job in an ordered community is large; a conversation should be had about the extent to which the jump from then to now is or is not larger.

Even since 1995 (when this manifesto was published) the pace of life has changed substantially; mobile phones looked like this at the time.

57. The difference, we argue, is that modern man has the sense (largely justified) that change is imposed on him, whereas the 19th century frontiersman had the sense (also largely justified) that he created change himself, by his own choice. Thus a pioneer settled on a piece of land of his own choosing and made it into a farm through his own effort. In those days an entire county might have only a couple of hundred inhabitants and was a far more isolated and autonomous entity than a modern county is. Hence the pioneer farmer participated as a member of a relatively small group in the creation of a new, ordered community. One may well question whether the creation of this community was an improvement, but at any rate it satisfied the pioneer’s need for the power process.

As we discussed in the ‘Leftist Psychology’ part of this analysis, many, if not most, Leftists possess an external locus of control, feeling that events in their lives happen to them, rather than being a result of actions that they themselves have undertaken. Now, to an extent they cannot really be blamed for this—the ratio of people possessing an internal versus an external locus of control has presumably declined radically as a consequence of the industrial revolution. As the techno-industrial system entrenches itself ever more fully, as individual and community autonomy is eroded and humanity is moulded to better suit the needs of the system, it is only natural that many would develop a sense of helplessness and defeatism. It’s no wonder that alongside the exponential development of technology, as the system grows ever more complex and globally interconnected, the digital behemoth inspires dread and apathy in the average man.

58. It would be possible to give other examples of societies in which there has been rapid change and/or lack of close community ties without the kind of massive behavioral aberration that is seen in today’s industrial society. We contend that the most important cause of social and psychological problems in modern society is the fact that people have insufficient opportunity to go through the power process in a normal way. We don’t mean to say that modern society is the only one in which the power process has been disrupted. Probably most if not all civilized societies have interfered with the power process to a greater or lesser extent. But in modern industrial society the problem has become particularly acute. Leftism, at least in its recent form, is in part a symptom of deprivation with respect to the power process.

Recall the power process. Goal; effort; attainment of goal; autonomy. Autonomy has probably been the aspect worst affected by modernity. Freedom itself has been steadily eroded as the technological system grows ever larger. CCTV cameras watch our every move; physical interaction with friends and family has become far less common; we are often too depressed after work to even consider doing anything satisfying or productive. Note that the above examples are not really tied directly to technological progress per se, rather the socio-cultural arrangement that stems from it (it is possible to imagine an advanced civilisation without CCTV cameras, and with a system of production which does not destroy the souls of its workers). But Ted believes that culture is inextricably tied up with the technological basis of society, and so it appears that the social and psychological deprivation of modernity is inevitable as long as present material conditions persist. I’m inclined to agree, as the aforementioned hypothetical advanced state strikes me as very idealistic considering the inevitable social effects of material changes.

Disruption of the Power Process in Society

59. We divide human drives into three groups: (1) those drives that can be satisfied with minimal effort; (2) those that can be satisfied but only at the cost of serious effort; (3) those that cannot be adequately satisfied no matter how much effort one makes. The power process is the process of satisfying the drives of the second group. The more drives there are in the third group, the more there is frustration, anger, eventually defeatism, depression, etc.

60. In modern industrial society natural human drives tend to be pushed into the first and third groups, and the second group tends to consist increasingly of artificially created drives.

61. In primitive societies, physical necessities generally fall into group 2: They can be obtained, but only at the cost of serious effort. But modern society tends to guarantee the physical necessities to everyone in exchange for only minimal effort, hence physical needs are pushed into group 1. (There may be disagreement about whether the effort needed to hold a job is “minimal”; but usually, in lower- to middle-level jobs, whatever effort is required is merely that of obedience. You sit or stand where you are told to sit or stand and do what you are told to do in the way you are told to do it. Seldom do you have to exert yourself seriously, and in any case you have hardly any autonomy in work, so that the need for the power process is not well served.)

62. Social needs, such as sex, love and status, often remain in group 2 in modern society, depending on the situation of the individual. But, except for people who have a particularly strong drive for status, the effort required to fulfill the social drives is insufficient to satisfy adequately the need for the power process.

63. So certain artificial needs have been created that fall into group 2, hence serve the need for the power process. Advertising and marketing techniques have been developed that make many people feel they need things that their grandparents never desired or even dreamed of. It requires serious effort to earn enough money to satisfy these artificial needs, hence they fall into group 2. Modern man must satisfy his need for the power process largely through pursuit of the artificial needs created by the advertising and marketing industry, and through surrogate activities.

A very astute observation is made here. Those desires which are most targeted by advertising and marketing are those which fall into the second group of Kaczynski’s human drives framework: ‘those that can be satisfied but only at the cost of serious effort’. He points out that the desires for ‘sex, love, and status’ fall into group two, and it is no coincidence that much of modern advertising sells exactly these: “buy our product and beautiful women will find you attractive!”

We will avoid a long tangent here because there is nothing to be said that can top documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis’ contribution to the matter; see his series ‘The Century of the Self’ wherein it is explored how Edward Bernays—Sigmund Freud’s nephew—applied psychoanalysis to marketing, reshaping the course of modern capitalist systems forever. Just one Curtis quote: “Although we feel we are free, in reality, we—like the politicians—have become the slaves of our own desires.”

64. It seems that for many people, maybe the majority, these artificial forms of the power process are insufficient. A theme that appears repeatedly in the writings of the social critics of the second half of the 20th century is the sense of purposelessness that afflicts many people in modern society. (This purposelessness is often called by other names such as “anomie” or “middle-class vacuity.”) We suggest that the so-called “identity crisis” is actually a search for a sense of purpose, often for commitment to a suitable surrogate activity. It may be that existentialism is in large part a response to the purposelessness of modern life. Very widespread in modern society is the search for “fulfillment.” But we think that for the majority of people an activity whose main goal is fulfillment (that is, a surrogate activity) does not bring completely satisfactory fulfillment. In other words, it does not fully satisfy the need for the power process. That need can be fully satisfied only through activities that have some external goal, such as physical necessities, sex, love, status, revenge, etc.

Ted is right to suggest that the identity crisis is actually a search for a sense of purpose. It’s clear that the urge—most prominent among leftists—to literally ‘reinvent’ themselves and to find an ever-expanding collection of labels with which to identify is a symptom of a lack of genuine social connection and the identity formation which would previously have been derived from it. As a result of the decimation of real community, the condition of man is becoming a ‘rootless’ one.

With no ties to anything tangible, we become what David Goodhart calls ‘anywheres’—people whose sense of identity is founded on abstractions—when a deep sense of fulfilment has always been found in being ‘somewheres’; people are rooted in a time and a place which impart their sense of identity to them, and who care more about those they exist among than abstract conceptions of community which are timeless, formless, and placeless.

With the death of community came the death of a stable, grounded sense of identity and purpose. Technology and liberalism may have made us ‘free’, but they have actually left us un-anchored; drifting, atomised, with nowhere—and no one—to call home. We now define ourselves by our consumer choices and our jobs rather than by our social relationships with those whom we exist among, and our connection to the land and nation which gave birth to us.

As far as existentialism being ‘in large part a response to the purposelessness of modern life’, this is indisputable; the Existentialists say this themselves. Specifically, it arose as a response to the decline of Christianity, and as a rejection of the philosophy of essentialism—the metaphysical position that all things have an ‘essence’ which makes that thing what it is, and without which it could not be considered to be that thing. Essentialism as applied to humanity takes a position wherein one’s individual essence is seen as a defining characteristic which is already determined at the moment of one’s conception. That is to say that, essence precedes existence.

But the reason the Existentialists rejected essentialism was due to their atheistic preconceptions—as Jean-Paul Sartre stated: “There is no human nature since there is no God to conceive it.” Without God, there are—and can be—no essences. Thus, in their conception, we are free to determine our own essence: ‘existence precedes essence’; not the other way around. Hence the fundamentally leftist nature of existentialism: hierarchical social arrangements are no longer seen as conducive to the fact of human difference and as an adherence to the natural order of superiority and inferiority among men. Instead, as obstacles to the pursuit of self-creation, social barriers, taboos, and hierarchies start to be perceived as oppressive in their apparently unfair restrictions on certain modes of being and in the self-determination of essence.4

Recall of course, that the most well-known Existentialists—Sartre and de Bouvoir—were among many other French intellectuals who signed the 1977 petition calling for the abolition of age of consent laws on the grounds that criminalising sexual relations between minors and adults infantalised the minors and stripped them of bodily autonomy. It is clear that existentialism did not simply aim to win greater freedom for individuals and allow them to chart their own paths in life, free of outdated hierarchical social restrictions. It was, in fact, an attack on the very foundations of morality itself. It was a movement of pure social constructivism: there is no human nature, we define ourselves; there is no objective morality, we define it ourselves; there are no essences, we define them ourselves.

Existentialism unconsciously seeped into modern culture in direct correlation with the decline of Christian belief. With the ‘death of God’, it was predictable that society should steadily move in a more subjectivist direction. The effects of this trend are evident when looking at the myriad forms of self-identification, the widespread ‘blank-slateism’ with regard to human difference, and the worrying growth of the complete rejection of fixed categorisation with regard to gender, sex, sexuality, and so on.

Queer Theory is itself a political expression of existentialist doctrine—positing the queer life of “an identity without essence” as an emancipatory mode of being which rejects the common forms of categorisation which adherents deem bourgeois, oppressive, and patriarchal. Concerted attempts to critique and deconstruct identity categories are designed to render them absurd in order to discard them. Fortunately, such categories are so deeply ingrained in human experience—because they are true—that such attacks have not been quite as effective as the queer theorists would hope. (The refrain, “a woman is someone who identifies as a woman”, is palpably absurd even to the layman). We cannot afford to let our guard down, however; attempts to shape public thought in this direction will lead to catastrophe if successful and must be vigilantly opposed.

Clearly, a mixed approach to the question of essentialism versus existentialism is warranted. I would propose that a form of dynamic essentialism works best: individuals have an essence which defines their individuality and sets down the rough path which they will navigate through their life. Though there is a fair bit of room for manoeuvre, individuals and groups possess certain innate characteristics which lead them to greater propensities, for better or worse, in terms of behaviour, socio-cultural arrangement, educational attainment, mental acuity, and so on.

Relating back to the earlier discussion of dialectical materialism, we can say that each individual possesses his own ‘base’—his ‘hardware’, determined by his genetics—but the ‘superstructure’—his upbringing, life events, certain socio-cultural and socio-economic factors—will have a large influence on the course of his life too. We should bear in mind, though, that the universe is not mechanistic. The individual ultimately determines much of his own life (within his pre-determined constraints), and overcoming whatever shortfalls may affect him in his environment is a large part of growth and individual development.

65. Moreover, where goals are pursued through earning money, climbing the status ladder or functioning as part of the system in some other way, most people are not in a position to pursue their goals autonomously. Most workers are someone else’s employee and, as we pointed out in paragraph 61, must spend their days doing what they are told to do in the way they are told to do it. Even most people who are in business for themselves have only limited autonomy. It is a chronic complaint of small business persons and entrepreneurs that their hands are tied by excessive government regulation. Some of these regulations are doubtless unnecessary, but for the most part government regulations are essential and inevitable parts of our extremely complex society. A large portion of small business today operates on the franchise system. It was reported in the Wall Street Journal a few years ago that many of the franchise-granting companies require applicants for franchises to take a personality test that is designed to exclude those who have creativity and initiative, because such persons are not sufficiently docile to go along obediently with the franchise system. This excludes from small business many of the people who most need autonomy.

66. Today people live more by virtue of what the system does for them or to them than by virtue of what they do for themselves. And what they do for themselves is done more and more along channels laid down by the system. Opportunities tend to be those that the system provides, the opportunities must be exploited in accord with the rules and regulations, and techniques prescribed by experts must be followed if there is to be a chance of success.

67. Thus the power process is disrupted in our society through a deficiency of real goals and a deficiency of autonomy in the pursuit of goals. But it is also disrupted because of those human drives that fall into group 3: the drives that one cannot adequately satisfy no matter how much effort one makes. One of these drives is the need for security. Our lives depend on decisions made by other people; we have no control over these decisions and usually we do not even know the people who make them. (“We live in a world in which relatively few people—maybe 500 or 1,000— make the important decisions,” Philip B. Heymann) Our lives depend on whether safety standards at a nuclear power plant are properly maintained; on how much pesticide is allowed to get into our food or how much pollution into our air; on how skillful (or incompetent) our doctor is; whether we lose or get a job may depend on decisions made by government economists or corporation executives; and so forth. Most individuals are not in a position to secure themselves against these threats to more than a very limited extent. The individual’s search for security is therefore frustrated, which leads to a sense of powerlessness.

68. It may be objected that primitive man is physically less secure than modern man, as is shown by his shorter life expectancy; hence modern man suffers from less, not more than the amount of insecurity that is normal for human beings. But psychological security does not closely correspond with physical security. What makes us feel secure is not so much objective security as a sense of confidence in our ability to take care of ourselves. Primitive man, threatened by a fierce animal or by hunger, can fight in self-defense or travel in search of food. He has no certainty of success in these efforts, but he is by no means helpless against the things that threaten him. The modern individual on the other hand is threatened by many things against which he is helpless; nuclear accidents, carcinogens in food, environmental pollution, war, increasing taxes, invasion of his privacy by large organizations, nationwide social or economic phenomena that may disrupt his way of life.

69. It is true that primitive man is powerless against some of the things that threaten him; disease for example. But he can accept the risk of disease stoically. It is part of the nature of things, it is no one’s fault, unless it is the fault of some imaginary, impersonal demon. But threats to the modern individual tend to be man-made. They are not the results of chance but are imposed on him by other persons whose decisions he, as an individual, is unable to influence. Consequently he feels frustrated, humiliated and angry.

Kaczinski makes an important distinction here. Events and dangers outside of our control do not necessarily have to be seen as threats to our autonomy. The distinction lies in whether these threats are natural (wild animals, hunger, natural disasters, etc.) or man-made. Almost all constraints on action and behaviour in the modern, sanitised, post-industrial world are man-made, and are thus the cause of greater psychological distress than natural ones, due precisely to their synthetic, contingent, and often somewhat petty nature. Freedom is never absolute, but always relative. In a world governed by the laws of nature and of physics, freedom is, by nature, only available within those pre-ordained boundaries which are unchanging and inflexible. But primitive man had an amount of autonomy within these constraints which is entirely unavailable to modern man. The contingent constraints set up by modern technological society—many of which are necessary for its continued functioning—restrict man’s autonomy in ways and to degrees never-before-seen in the history of humanity. I say all of this in a value-free sense; you may agree or disagree with Ted with regard to your opinion on the necessity of these constraints, but it is undeniable that autonomy has been eroded by industrial society, relative to more primitive times.

70. Thus primitive man for the most part has his security in his own hands (either as an individual or as a member of a small group), whereas the security of modern man is in the hands of persons or organizations that are too remote or too large for him to be able personally to influence them. So modern man’s drive for security tends to fall into groups 1 and 3; in some areas (food, shelter, etc.) his security is assured at the cost of only trivial effort, whereas in other areas he cannot attain security. (The foregoing greatly simplifies the real situation, but it does indicate in a rough, general way how the condition of modern man differs from that of primitive man.)

Ted’s point here is that the elements of the power process are out of balance. As he says, the needs for food and shelter are met with only trivial effort—removing the fulfillment of the power process thereby attained—while other elements cannot be met at all, causing chronic psychological distress in post-industrial man.

71. People have many transitory drives or impulses that are necessarily frustrated in modern life, hence fall into group 3. One may become angry, but modern society cannot permit fighting. In many situations it does not even permit verbal aggression. When going somewhere one may be in a hurry, or one may be in a mood to travel slowly, but one generally has no choice but to move with the flow of traffic and obey the traffic signals. One may want to do one’s work in a different way, but usually one can work only according to the rules laid down by one’s employer. In many other ways as well, modern man is strapped down by a network of rules and regulations (explicit or implicit) that frustrate many of his impulses and thus interfere with the power process. Most of these regulations cannot be dispensed with, because they are necessary for the functioning of industrial society.

72. Modern society is in certain respects extremely permissive. In matters that are irrelevant to the functioning of the system we can generally do what we please. We can believe in any religion we like (as long as it does not encourage behavior that is dangerous to the system). We can go to bed with anyone we like (as long as we practice “safe sex”). We can do anything we like as long as it is unimportant. But in all important matters the system tends increasingly to regulate our behavior.

73. Behavior is regulated not only through explicit rules and not only by the government. Control is often exercised through indirect coercion or through psychological pressure or manipulation, and by organizations other than the government, or by the system as a whole. Most large organizations use some form of propaganda to manipulate public attitudes or behavior. Propaganda is not limited to “commercials” and advertisements, and sometimes it is not even consciously intended as propaganda by the people who make it. For instance, the content of entertainment programming is a powerful form of propaganda. When someone approves of the purpose for which propaganda is being used in a given case, he generally calls it “education” or applies to it some similar euphemism. But propaganda is propaganda regardless of the purpose for which it is used. An example of indirect coercion: There is no law that says we have to go to work every day and follow our employer’s orders. Legally there is nothing to prevent us from going to live in the wild like primitive people or from going into business for ourselves. But in practice there is very little wild country left, and there is room in the economy for only a limited number of small business owners. Hence most of us can survive only as someone else’s employee.

74. We suggest that modern man’s obsession with longevity, and with maintaining physical vigor and sexual attractiveness to an advanced age, is a symptom of unfulfillment resulting from deprivation with respect to the power process. The “mid-life crisis” also is such a symptom. So is the lack of interest in having children that is fairly common in modern society but almost unheard-of in primitive societies.

75. In primitive societies life is a succession of stages. The needs and purposes of one stage having been fulfilled, there is no particular reluctance about passing on to the next stage. A young man goes through the power process by becoming a hunter, hunting not for sport or for fulfillment but to get meat that is necessary for food. (In young women the process is more complex, with greater emphasis on social power; we won’t discuss that here.) This phase having been successfully passed through, the young man has no reluctance about settling down to the responsibilities of raising a family. (In contrast, some modern people indefinitely postpone having children because they are too busy seeking some kind of “fulfillment.”

We suggest that the fulfillment they need is adequate experience of the power process—with real goals instead of the artificial goals of surrogate activities.) Again, having successfully raised his children, going through the power process by providing them with the physical necessities, the primitive man feels that his work is done and he is prepared to accept old age (if he survives that long) and death. Many modern people, on the other hand, are disturbed by the prospect of physical deterioration and death, as is shown by the amount of effort they expend trying to maintain their physical condition, appearance and health. We argue that this is due to unfulfillment resulting from the fact that they have never put their physical powers to any practical use, have never gone through the power process using their bodies in a serious way.

This gets to the heart of what the power process is, and why the replacement of real goals with surrogate activities is so common in the modern world: all of those things which genuinely fulfill the power process are disrupted, either by being made trivial or impossible. In return, surrogate activities are sold to us by the system in exchange for the resources to continue its functioning. Though Ted does not state it explicitly, the power process has essentially been captured by capitalism and a formula has been calculated to extract the most control and profit from those most susceptible to short-term gratification and addiction to the never-completely-satisfying surrogate activities on offer. These surrogate activities can, of course, never be of the sort which present a genuine threat to the system. Thus, we are not only sold distraction and pacification, but our distraction and pacification are consciously designed to further entrench the system itself. It is a constant cycle of reinforcement and centralisation of power.

It is not the primitive man, who has used his body daily for practical purposes, who fears the deterioration of age, but the modern man, who has never had a practical use for his body beyond walking from his car to his house. It is the man whose need for the power process has been satisfied during his life who is best prepared to accept the end of that life.

76. In response to the arguments of this section someone will say, “Society must find a way to give people the opportunity to go through the power process.” This won’t work for those who need autonomy in the power process. For such people the value of the opportunity is destroyed by the very fact that society gives it to them. What they need is to find or make their own opportunities. As long as the system gives them their opportunities it still has them on a leash. To attain autonomy they must get off that leash.

How Some People Adjust

77. Not everyone in industrial-technological society suffers from psychological problems. Some people even profess to be quite satisfied with society as it is. We now discuss some of the reasons why people differ so greatly in their response to modern society.

78. First, there doubtless are innate differences in the strength of the drive for power. Individuals with a weak drive for power may have relatively little need to go through the power process, or at least relatively little need for autonomy in the power process. These are docile types who would have been happy as plantation darkies in the Old South. (We don’t mean to sneer at the “plantation darkies” of the Old South. To their credit, most of the slaves were not content with their servitude. We do sneer at people who are content with servitude.)

79. Some people may have some exceptional drive, in pursuing which they satisfy their need for the power process. For example, those who have an unusually strong drive for social status may spend their whole lives climbing the status ladder without ever getting bored with that game.

80. People vary in their susceptibility to advertising and marketing techniques. Some people are so susceptible that, even if they make a great deal of money, they cannot satisfy their constant craving for the shiny new toys that the marketing industry dangles before their eyes. So they always feel hard-pressed financially even if their income is large, and their cravings are frustrated.

81. Some people have low susceptibility to advertising and marketing techniques. These are the people who aren’t interested in money. Material acquisition does not serve their need for the power process.

82. People who have medium susceptibility to advertising and marketing techniques are able to earn enough money to satisfy their craving for goods and services, but only at the cost of serious effort (putting in overtime, taking a second job, earning promotions, etc.). Thus material acquisition serves their need for the power process. But it does not necessarily follow that their need is fully satisfied. They may have insufficient autonomy in the power process (their work may consist of following orders) and some of their drives may be frustrated (e.g., security, aggression). (We are guilty of oversimplification in paragraphs 80-82).

83. Some people partly satisfy their need for power by identifying themselves with a powerful organization or mass movement. An individual lacking goals or power joins a movement or an organization, adopts its goals as his own, then works toward these goals. When some of the goals are attained, the individual, even though his personal efforts have played only an insignificant part in the attainment of the goals, feels (through his identification with the movement or organization) as if he had gone through the power process. This phenomenon was exploited by the Fascists, Nazis and Communists. Our society uses it too, though less crudely. Example: Manuel Noriega was an irritant to the U.S. (goal: punish Noriega). The U.S. invaded Panama (effort) and punished Noriega (attainment of goal). The U.S. went through the power process and many Americans, because of their identification with the U.S., experienced the power process vicariously. Hence the widespread public approval of the Panama invasion; it gave people a sense of power. We see the same phenomenon in armies, corporations, political parties, humanitarian organizations, religious or ideological movements. In particular, leftist movements tend to attract people who are seeking to satisfy their need for power. But for most people identification with a large organization or a mass movement does not fully satisfy the need for power.

It is very interesting here that Kaczynski enlarges the scope of the power process to explain that it is not a purely individual phenomenon. Of course, it makes sense that, through identification with the collective, the individuals within it can take a sense of fulfillment from the achievement of collective aims. As he states, political movements and nation states can use this to great effect. This is, of course, a synthetic extrapolation of the sort of organic fulfillment found in the collective striving and achievement of the tribe. He doesn’t explore this here, but I would wager that the synthetic fulfillment found in national achievement is much diminished in comparison to the organic fulfillment found in the collective achievement of the primitive tribe, even if the goal and its attainment were technically more easily achieved than, for example, the logistical and organisational miracle of success in modern warfare. I base this on the assumption that one would find greater fulfillment in being a larger part of a smaller project, especially when the effort put into the attainment of the goal is undertaken as part of an intimate group in which all involved are actually familiar with and mutually dependent on one another.

84. Another way in which people satisfy their need for the power process is through surrogate activities. As we explained in paragraphs 38–40, a surrogate activity is an activity that is directed toward an artificial goal that the individual pursues for the sake of the “fulfillment” that he gets from pursuing the goal, not because he needs to attain the goal itself. For instance, there is no practical motive for building enormous muscles, hitting a little white ball into a hole or acquiring a complete series of postage stamps. Yet many people in our society devote themselves with passion to bodybuilding, golf or stamp-collecting.

Some people are more “other-directed” than others, and therefore will more readily attach importance to a surrogate activity simply because the people around them treat it as important or because society tells them it is important. That is why some people get very serious about essentially trivial activities such as sports, or bridge, or chess, or arcane scholarly pursuits, whereas others who are more clear-sighted never see these things as anything but the surrogate activities that they are, and consequently never attach enough importance to them to satisfy their need for the power process in that way. It only remains to point out that in many cases a person’s way of earning a living is also a surrogate activity. Not a pure surrogate activity, since part of the motive for the activity is to gain the physical necessities and (for some people) social status and the luxuries that advertising makes them want. But many people put into their work far more effort than is necessary to earn whatever money and status they require.

85. In this section we have explained how many people in modern society do satisfy their need for the power process to a greater or lesser extent. But we think that for the majority of people the need for the power process is not fully satisfied. In the first place, those who have an insatiable drive for status, or who get firmly “hooked” on a surrogate activity, or who identify strongly enough with a movement or organization to satisfy their need for power in that way, are exceptional personalities. Others are not fully satisfied with surrogate activities or by identification with an organization.

In the second place, too much control is imposed by the system through explicit regulation or through socialization, which results in a deficiency of autonomy, and in frustration due to the impossibility of attaining certain goals and the necessity of restraining too many impulses.

86. But even if most people in industrial-technological society were well satisfied, we would still be opposed to that form of society, because (among other reasons) we consider it demeaning to fulfill one’s need for the power process through surrogate activities or through identification with an organization, rather than through pursuit of real goals.

In the next instalment of this series, we will take a further look at Kaczynski’s conception of freedom, as well as his philosophy of history and analysis of revolution, exemplified in his ‘principles of history’.

In the final two paragraphs of the first chapter in The Spirit of Conservatism, Vol II, I outline other ways in which I believe scientific and technological development do damage to our humanity.

Biologists do not classify male and female simply according to ‘XX’ and ‘XY’, as many believe. There are, of course, intersex people born with various other sets of chromosomes. The determining factor is the Y chromosome, the absence of which means female and the presence of which means male. Those with Klinefelter Syndrome (XXY chromosomes), for example, are male.

See the ‘Leftist Metaphysics’ chapter in The Spirit of Conservatism.

See the ‘Leftist Metaphysics’ chapter in The Spirit of Conservatism.